Ursula Lennox, the Remedial Project Manager for the Agriculture Street Landfill Superfund Site, has been coming to Gordon Plaza since the 1990s.

“This was my first landfill,” she says.

In 1994, the site where the community of Gordon Plaza and the Press Park housing development were built on top of the former Agriculture Street Landfill, was put on the national priorities list of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act, also known as the Superfund. In 2002, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) performed remediation. They excavated millions of cubic feet of soil, laid down a permeable mat, and replaced the soil. This occurred on the yards of complying homeowners; it was not compulsory and did not include land below the slabs the homes sit on, nor the land beneath the school, community center in Press Park, or the roads.

Every five years, the EPA returns to the site to test for detectable contaminants in residents’ homes as well as the surrounding soil. So Lennox, and one of her coworkers, Jannetta Coats, who works in community involvement for the EPA, know members of the Gordon Plaza community quite well. Lennox was in contact with Shannon Rainey, the President for Residents of Gordon Plaza, LLC after Rainey began to notice a rank smell coming through the pipes in her home.

“When she complained of the odors in her home, that’s why we’re here today.”

As a technician set up canisters with intake tubes that would monitor the for certain contaminants, Rainey swapped stories with the EPA’s representatives. They cracked jokes and speculated about what they would do with the giant lottery pot, which at that point had not been won.

“You remember Johnnie Jackson?” asked Rainey.

“He kept insisting that this wasn’t on top of a toxic landfill, denied that there was a cancer risk… he died of cancer,” continued Rainey.

The EPA had already been back to Gordon Plaza for the fourth 5 year-report. This time around they were testing for Polynuclear Aromatic Hydrocarbons, Methane and Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs).

I asked Lennox whether the cost of continuous monitoring (the EPA had flown Lennox and Coats out from the regional office in Dallas) not to mention the initial massive cleanup that the EPA did in 2002 exceeding the cost of relocation raised eyebrows at the EPA, and she responded:

“The EPA rarely buys out communities… that’s not in our mission. There is a very low number of examples of this in the EPAs history.”

She pointed to one example, that of Escambia, Florida where 358 households won funded relocation from the EPA (their allocation was 18 million).

Jesse Perkins, a Gordon Plaza resident who worked for the Sewerage and Water Board for two decades, takes a less kind view of the EPA’s cleanup efforts.

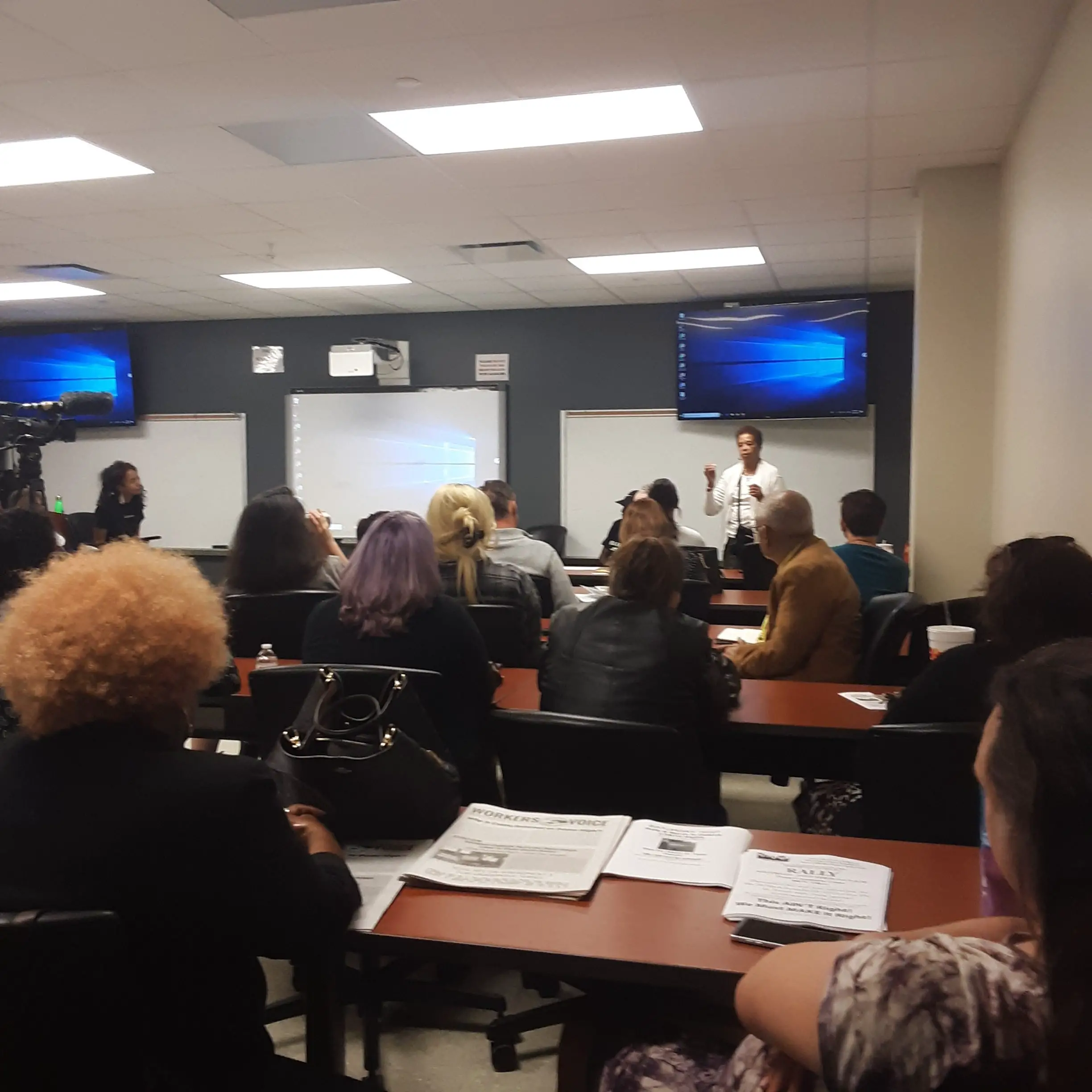

“It was a cover-up,” he told attendees at Community Forum on Gordon Plaza Relocation, which was held at Delgado College near the Gordon Plaza site.

“The EPA maybe wasn’t an ally to the city, but no one was an ally to us,” he continued. At 27, Perkins bought his home at an auction, making him one of the youngest homeowners in Gordon Plaza. Believing that replacing the top layer of soil was not a real solution, Perkins refused to allow the EPA to perform the remediation on his land.

“Three, four mayors have turned their back on us,” he continued.

Mayor Latoya Cantrell is just the latest in a series of non-responsive mayoral administration – currently, her administration has refused to meet with members of the community, or comment on Gordon Plaza, citing ongoing litigation as their reason for not engaging. Meanwhile, buildings housing new tenants are going up on the grounds of the old Agriculture Street landfill. Rainey speculates that the tenants have no idea the toxic history of their new apartments.

“People don’t know we live there!” says Marylin Lamar, a community member and activist living in Gordon Plaza.

“I call [the city] about the grass, the trash… people leave trash, and abandon stolen cars in our community.”

However, it seems that the city has noticed the spate of actions occurring around Gordon Plaza. More than a decade after closing off the city-owned buildings at Press Park, the city has begun to demolish the development.

“I didn’t even know about it until it started happening,” said Joe Fortner, the current Director of the Housing Authority of New Orleans (HANO).

“That’s the work of the city.” He added nebulously.

Activist Angela Kinlaw also noted that the grass was cut around Press Park before a large demonstration that took place there in September. Not only that, but Rainey reported that a representative from city hall had contacted her, asking about what sums of money the residents wanted for relocation. Though promising, this incremental movement has come after decades of struggle.

“We have been abused by lawyers, the mayors and council members!” says Lywina Hurst, a resident of Gordon Plaza who also spoke at the forum. Both Hurst and Lamar are breast cancer survivors.

One resident who grew up in Gordon Plaza told the forum that the neighbor to her left and right both died, as well as her mother, who left the house to her. She is now raising her two children there.

“That was my childhood, watching people die around me. Now my daughters’ childhood, they can’t go outside.” She held a tiny baby to her chest as she spoke. Her elder daughter stood on a chair beside her, wearing a green school uniform with her hair braided neatly.

While the residents’ children are told not to play outside, and residents note large snakes emerging from the newly-cut grass, the city continues to invest in piecemeal renovations to the 54-houselhold community—demolishing press Park, mowing the grass, and adding ADA-compliant curb cuts to the sidewalk. Residents would rather see that money go towards relocation, and they worry about the workers who are digging in the earth and razing the old structures. If each household received 400,000 for relocation (Rainey informed Big Easy Mag that 375,000-400,000 is the current ask) then the cost to the city would be $21,600,000. This is less than ten percent of the proposed renovations to the Superdome, and less than half of what the Morial Convention Center receives in dedicated taxes every year.

Says Kinlaw, “Slavery ended because people who had been enslaved for generations, in their spirit said ‘this is not right.’ If the enslaved people didn’t rise up, we’d still be there today. Every victory comes because someone was willing to rise up against the system as it is… Justice delayed is justice denied.”

Jesse Lu Baum is a queer writer and cartoonist originally from Brooklyn, New York. Her writing has been featured in publications such as Medium.com, The Jewish Daily Forward, The Mid-City Messenger and Preservation in Print. Aside from writing, she has also worked as a non-profit home repair person, a theater bartender, and a research assistant. If you liked this piece, you should check out Jesse’s other work here.